In a field due north of Chagford off a minor road leading to the village of Drewsteignton

there stands an unusual structure consisting of a large stone slab or capstone supported by

three upright stones. This is Spinster's Rock, the best surviving example in Devon

of a neolithic burial chamber known as a dolmen or cromlech. Three stones are necessary and

sufficient to support the capstone of a dolmen, though instances of these megalithic

antiquities with more than three supports exist.

Now, as a general rule under such circumstances, three points of support, and three only,

will be found to be effective; hence any of the enclosing stones can be removed, provided

that three are left so placed that the centre of gravity of the capstone falls within the

triangle formed by their points of contact with it. [R Hansford Worth, p468]

The word dolmen is derived from the Celtic words daul, a table, and maen,

a stone. Typically dolmens were covered with earth or smaller stones to form a barrow which

in this case has weathered away, leaving only the stones of the burial mound intact. When

first mapped by archaeologists Spinster's Rock was surrounded by a number of other stones

arranged in circles and rows which may have been added after the dolmen was erected, but

these have now disappeared.

The dolmen's name derives from the legend that three spinsters had time to kill one

morning before breakfast while waiting for the jobber to call and collect the woollen cloth they had spun.

These indefatigable wool-spinners, who were not spinsters in the unmarried sense, decided to

while away the time by artfully balancing a few large stones in an upright position.

The first written account of this legend referring to Spinster's Rock was by William

Chapple who in 1778 interrupted his work on the preparation of a "correct" version of

Tristram Risdon's Survey of Devon to write a book about this antiquity.

Unfortunately he died the following year before either book was published, though the

manuscript concerning the cromlech was already in the hands of a printer. They produced an

advertisement to promote this book that referred to the supposed Druidical significance of

the dolmen; the italicised part is the book's full title:

The Description and Exegesis of a very remarkable Cromlech, hitherto preserved entire,

on Shilston Farm, in the parish of Drewsteignton, Devon: Demonstrating the surprising

accuracy of its geometric and astronomic construction; ascertaining its antiquity and

primary use; and examining how far it might become accidentally subservient to the

superstition of the Druids, and to what purposes afterwards applied by the Romans, or by

some Romanized Britons and Pagan Saxons.

There is more about Tristram Risdon and William Chapple on the Early Devon Topographers page.

Born in Ashburton in 1752, the son of surgeon Nicholas Tripe, John inherited a large

fortune on condition he changed his name to Swete. This allowed him to indulge his passion

for the countryside of his native Devon, and over the years between 1789 and 1800 he made a

series of tours across the county, writing up what he saw in 20 journals which he called

Picturesque Sketches of Devon. These were lavishly illustrated with watercolours

painted by his own hand in the style of his contemporary, the Plymouth landscape painter

William Payne.

The tour covered by the first journal took Swete along the eastern edge of Dartmoor, giving

him the opportunity for a detailed examination of the Drewsteignton antiquities including

Spinster's Rock. As in many of his paintings, his depiction of the dolmen included an image

of himself wearing a distinctive hat. There are no known paintings of Swete by other

artists, so this may not be a true likeness, but from his description of the cromlech he

was surely behatted at the time.

We now remounted, and after a return of half a mile, we left Drewsteignton towards the

east, and rejoined the public road we had quitted near the bridge - a ride of about two

miles brought us in sight of the famous cromlêk, which is certainly one of the most

perfect in the world - it stands in a field belonging to a farm called, (perhaps from this

curious monument) Shel-stone. The covering stone or quoit hath three supporters - it rests

on the pointed tops of the southern and western one, but that on the north side upholds it

on its inclining surface somewhat below the top; its exterior side rising several inches

higher that the inner part on which the superimpendent stone is laid: this latter supporter

is 7 feet high; indeed they are all of them of such an altitude, that I had not the least

difficulty in passing under the covering stone, erect, and with my hat on. [10, p16]

Swete expressed caution in ascribing any Druidical significance to the monument while

concurring with the Cornish antiquarian William Borlase that this dolmen was likely to have

been erected above a burial chamber, as in other instances bones have been found in the

vicinity.

That these monuments have been erected by the Britons there can be no doubt - how true the

conjecture may be that they were Druid altars, and of old applied to sacrificial uses, at

this remote period of time can never be well ascertained. Borlase and others who have

treated on this subject judge them to have been sepulchral monuments; and there is reason

for the supposition, inasmuch as they are often found on burrows - indeed, in Ireland, the matter hath been sufficiently

elucidated - for there (though Borlase failed in his search in Cornwall) bones were

absolutely found in the area, which some of them enclosed - it rests therefore on

probability that, to whatever other purposes it might have been applied, the use and intent

of the cromlêk - that is crooked stone, was primarily to distinguish and to do honour

to the dead... [10, p17]

This was a period when it was fashionable to interpret the standing stone antiquities of

Dartmoor as Druid monuments: Samuel Rowe in his much admired 1848 work A Perambulation of

Dartmoor gives a thorough account of the various ideas put forward on the possible

Druidical significance of the Drewsteignton cromlech by earlier writers such as Borlase,

Chapple, and Polwhele, among others [Rowe, p39-43]. Rowe accepted that its primary function

was of a sepulchral nature, but was open to the possibility of it being a Druid altar where

sacrificial offerings were made.

By the end of the 19th century, mainstream thinking had turned against the Druidical view,

and Samuel's nephew J. Brooking Rowe inserted this disclaimer in the preface to his

expanded edition of the Perambulations published in 1896:

I have made many alterations and some additions, but, although entirely disagreeing with

them, I did not feel at liberty to eliminate altogether the Druidical theories of the

author with which the first edition of the book was saturated.

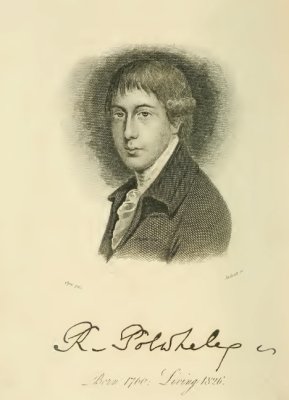

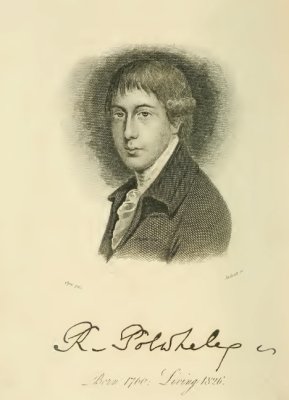

Richard Polwhele [6, Vol 1, p150] gives this description of the stone rows and circles

that were once seen in the vicinity of the dolmen but have now vanished. The beginning of

this account has a striking similarity to one given earlier by Swete, who is credited in a

Devon & Cornwall Notes & Queries article as being the first to document these

latterly despoiled antiquities [8, p88-93]:

Towards the west of the cromlech I remarked several conical pillars about four foot high.

On the fourth side there are three, standing in a direct line from east to west. With

respect to columns erected on a circular plan, the number of stones erect are various. The

distance of the pillars from each other is different in different circles, but is the same,

or nearly so, in one and the same circle.

Swete's account begins:

In an adjoining field towards the west I remarked several conical pillars about four foot

high - on the southern side there are three standing in a direct line from east to west -

the distance from the more western one, to the middle one was 212 paces...

Swete and Polwhele were near neighbours and the two men of letters established a rewarding

friendship based on mutual respect; Polwhele acknowledged Swete's help in preparing the

chapter on "The Indigenous Plants of Devonshire" in his History[6]. However, by

1796 their relationship had turned sour, ending in a public spat in the pages of the

Gentleman's Magazine, each accusing the other of plagiarism in their writings on

the Drewsteignton antiquities.

The argument became acrimonious and public through the Gentleman's Magazine and

European Magazine with Polwhele's suggestion that Swete had misappropriated his

research. Swete later wrote several letters to the editor of the Gentleman's

Magazine (e.g. The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle for the year 1796, volume

LXVI part 2, p896), reproaching him for printing the comments and argued that

Polwhele's claim of plagiarism was baseless given that Polwhele's information was derived

from his own volumes. In 1797 Polwhele was still complaining of 'Mr Swete's unhandsome

interference with my Druidical researches'. His particular objections were to Swete writing

on the Drewsteignton cromlech and the Logan Stones (in the River Teign nearby). note1

The eventually patched up their differences, but the relationship remained frosty.

Visiting Spinster's Rock, one is struck by the incongruity of such an imposing antiquity

standing in an otherwise unremarkable meadow. In the past it was arable land, and the

Victorian photographer Falcon, commenting on the location of the dolmen, dryly noted

that:

...this, the only Devonian standing cromlech, reigns in a potato field, or haply over turnips and mangolds. Its dignity somehow survives

the contest with those strenuous vegetables; but many must needs think congruity more

important than locality, and regret the domesticity of its setting. [Falcon, p x]

After an exceptionally wet year during which the field containing it had been furrowed by

ploughing, the dolmen collapsed in January 1862. Fortunately no-one was around at the time as

the capstone is said to weigh 16 tons! Some ingenious locals were able to reinstate it using

tools of Archemedian simplicity for which they were handsomely rewarded. The adjacent image

was produced from a photograph of the fallen cromlech taken on February 21st, 1862[11].

Here stands, on a farm called Shilstone, the only cromlech left in Devon, which once formed

the central feature of a group of stone circles and avenues. It fell in January, 1862, and

was 'restored' in the same year. Though the 'quoit' is two feet thick, fifteen in length,

and ten in breadth, a builder and a carpenter of Chagford, by the aid of pulleys and a

screw-jack, replaced it at a cost of £20

note 2; and thus very much reduced the vague wonder that commonly

attaches to the erection of such structures. [R.N.Worth, p324]

The re-erection of the fallen stones was possibly at the instigation of a local

antiquarian and geologist, George Wareing Ormerod, who observed the reconstruction and made

this sketch showing the wooden frame used to aid the raising of the capstone[11]. In her

History of Chagford, Jane Hayter-Hames writes of his preoccupation with the

antiquities of the parish of Chagford:

By profession a solicitor, this enthusiastic gentleman began [to take] an interest in

Spinster's Rock, in stone circles, stone rows and other pre-Roman remains, that helped to

attract the attention of visitors. ..... When the cromlech of Spinster's Rock collapsed in

January 1862 he helped to have it raised to its original position. Indeed, he was very

disappointed that only days previously he had been unable to photograph it due to bad

weather conditions. [Hayter-Hames, p110]

Ormerod's satisfaction at the timely restoration of the dolmen was tempered by the

realisation that the supporting stones were not in their original positions after all. Though

unable to photograph the dolmen, he had made a number of camera lucida

sketches in 1858 which provided the template for the restoration work. Three of these

sketches are shown alongside note3.

The dolmen was restored in November of 1862, but the restoration does not fully reproduce

the original form; the eastern stone has been placed almost at right angles to its original

position, and the capstone, instead of resting on the top of the northern support, rests in

a notch cut in its bevelled slope. [R Hansford Worth, p468]

There had been some suggestion that the fall of the dolmen resulted from foul play, but a

meticulous examination of the surroundings afterwards convinced Ormerod that this was not

the case. He regarded the inconsistencies in the reconstruction of the dolmen as a minor

irritant. Much more serious in his eyes was the removal at an earlier date of the nearby

stone circles and rows by the Shilstone tenant farmer. Ormerod's sketch of the dolmen after

its re-erection is shown above[11].

A mistake has been made in the restoration of the north-easterly support, but it is not of

much importance. Although, as I consider, the then tenant of Shilston Farm was free from

blame as regards [the collapse of] the cromlech, yet he has been guilty of an act which

every antiquary will regard as one of great atrocity. Polwhele mentions certain rude stones

as there existing, but though I have carefully examined the fields in the neighbourhood of

the cromlech, I could not find a trace of them. Early in 1872 I received the following

extract from the journal of my late friend, the Rev. W. Grey: " Wednesday, 4th July, 1838.

Visited from Moreton the Druidical circles above the cromlech. The cromlech lies in a field

about 110 yards to the east. There are two concentric circles of stones, the inner circle

having entrances facing the cardinal points, that to the north being sixty-five paces in

length and five broad. The outer circle, besides these, has avenues diverging towards

north-east, south-east, south-west, and north-west. A smaller circle seems to intersect the

larger, of which the avenue eastwards is very evident." I examined the field on March 22,

1872, when the field had been recently ploughed, and not a trace remained. The circles and

via

sacra had given place to the plough. On making inquiries, I found that the stones

had been removed prior to 1832; and that though the via sacra remained in 1848, the circles

had been removed [by then]

note4.

Rev. W. Grey provided Ormerod with this plan depicting the layout of the stone circles and

rows described above. The cromlech is marked to the east of the circles while Bradford Pool

is shown to their north-east. note5

Soon after the fall of the dolmen Ormerod visited the scene and noted that the upright

stones had been sunk no more than eighteen to twenty-four inches into the ground which was of

light granite gravel that had become sodden by recent heavy rain. He was also present during

the reconstruction and witnessed the steps taken to reduce the likelihood of another

collapse.

In the course of the re-erection, the ground on which the cromlech stood was excavated, and

a pavement made of large blocks of granite which fixed the uprights firmly in their places,

and to make them more secure a hole was cut horizontally through each of the uprights, in

which a thick bar of iron was placed resting on the granite pavement, and the whole

foundation was covered with earth.

note6

From Todd Gray's introduction to volume 1 of Swete's Travels in Georgian

Devon[10].

There seems to be some uncertainty as to who actually footed the £20 bill: according

to the sources quoted on the Spinster's Rock page on legendarydartmoor.co.uk, the cost of replacing

the capstone was met by either the Reverend William Ponsford, or by a certain Mrs Bragg.

Backing for Ponsford as the benefactor is to be found in the The Modern

Antiquarian which quotes a letter stating that the work was done "by Messrs. W. Stone

& Ball, builders at Chagford, at the expense of the Rev. W. Ponsford, the Rector of

Drewsteignton." However the scholarly Victoria History of Devon says the dolmen "was replaced

by the late Mrs Bragg, of Furlong" [7, p348].

When in doubt, who better to turn to than that respected authority on Dartmoor, William

Crossing. His Guide to Dartmoor points out the division of responsibility with

characteristic precision:

The expense of this was borne by the late Mrs. Bragg, of Furlong, the owner of Shilston,

and it was superintended by the rector, the Rev. William Ponsford. [Crossing, p274]

G Wareing Ormerod published these findings and the camera lucida sketches in a paper to the

Journal of the Royal Archaeological Society, vol.29, 1872. The three sketches shown were

reproduced in Worth's Dartmoor [5, p181].

Taken from an article entitled "Drewsteignton Cromlech" by G Wareing Ormerod that appeared

in The Antiquary, Vol. 3, 1880.

According to J Brooking Rowe, the last stones of these vanished antiquities disappeared in

1865 when the few then remaining were used in the building of a farmhouse in the

neighbourhood. [Rowe, p118]

Hansford Worth scanned the literature looking in vain for corroboration of Grey's findings.

Noting

Swete's late 18th century description[8] of these supposedly Druidical

remains, he remarks that Ormerod's plan of Grey's "discovery" shows 105 stones, far

exceeding the number in Swete's earlier account. To uphold the good name of archaeological

endeavour Worth exhorts us to dismiss Grey's elaborate but illusory schema as the product

of a fertile imagination:

It has long seemed to me that the time was overdue for someone in the interests of

archaeology, to deal in an even more summary manner with Rev. W. Grey's "discovery". There

is no evidence that prior to 9:30am on Wednesday, 4th July 1838, any person other than Grey

or his brother ever saw, or imagined that he saw, the remains which the pair conceived that

they then surveyed. And it is certain that no independent observer has since reported

having seen these remains; while it is, or should be, common knowledge that uninformed

enthusiasm can gravely over-stimulate the imagination. [Hansford Worth, p470]

An interesting in-depth review and analysis of the evidence for the existence and nature of

these remains is given in

Prehistoric Dartmoor Walks.

Quoted from "The fall and restoration of the Cromlech of Drewsteignton in the county of

Devon, 1862" by G Wareing Ormerod, Transactions of the Devonshire Association, Vol. 4

part2, p409-411, 1871.

A History of Devonshire by R.N. Worth, Elliot Stock, London, 1895.

Devon by W.G. Hoskins, Collins, 1954; new ed., Phillimore, 2003.

History of Chagford by Jane Hayter-Hames, Phillimore, 1981.

The Witchcraft and Folklore of Dartmoor by Ruth St.Leger-Gordon, Peninsula Press,

1994.

Worth's Dartmoor by R Hansford Worth, David & Charles, 1967. Hansford Worth

was the son of RN Worth cited in 1.

A History of Devonshire in 3 volumes by Richard Polwhele, London, 1793-1806;

facsimile reprint Kohler & Coombes, Dorking, 1977.

The Victoria History of the County of Devon volume 1, edited by William Page,

London, 1906.

Travels in Georgian Devon: The Illustrated Journals of the Reverend John Swete,

1789-1800 in four volumes, edited by Todd Gray and Margery Rowe, Devon Books, 1997.

Swete's commentary on Spinster's Rock and the nearby antiquities cited in [8] is found in

volume 1 of this magnificent set on pages 16-19.

Dartmoor Illustrated by T A Falcon, Exeter, 1900.

The 1792 watercolour 'Crom-lek at Drewsteignton' by Revd. John Swete is reproduced from

Volume 1 of

Travels in Georgian Devon [10, p17] by kind permission of the

copyright holders

Halsgrove

Publishing, the publishers of the Devon Books imprint.

The photograph showing the Devonshire Association meeting at Spinster's Rock in 1946 is

reproduced by kind permission of the Dartmoor Archive who own the copyright of this image.

It comes from the Taylor collection held in that archive. Information about this image and

its copyright can be seen on the

Dartmoor Trust website