This was a critical moment for the rebel leader Humphrey Arundell. His first attempt at

persuading Exeter's mayor John Blackaller to join the rebellion had fallen on deaf ears. Now

he had to decide whether or not to leave a contingent of his forces to hold Exeter while the

remainder marched to London to deliver their demands to the king. Given the size of his army

and the rudimentary weaponry at their disposal, he must have decided that this would leave

both detachments overexposed: he chose instead to deploy the entire rebel army in laying

siege to the city, a fateful decision as it transpired.

The siege proved to be the turning point of the campaign and the ruination of his plans,

for it meant surrendering the initiative and granting the government a desperately needed

breathing space during which to mobilise and take the measures to confine the operations to

the south-western peninsula. [Cornwall, p101]

The mayor was given an ultimatum by the leaders of the seditious horde assembled outside

the city walls. Unless he and the city's council would pledge unconditional support for the

rebels' demand for the reinstatement of the former religious practices, the city would remain

under siege until they capitulated.

Blackaller's resolve did not weaken and this new entreaty was summarily dismissed. Just as

when confronted by Perkin Warbeck's rebel army 52

years earlier, the people of Exeter in backing their mayor's defiant stance once again

demonstrated their loyalty to the crownnote1.

Aware that the majority of Exeter's citizens sided with them in matters of religion, the

rebels hoped that many would soon defect to their cause, leading to the fall of the city

before long. This would give them access to a plentiful supply of arms and victuals, as well

as potential recruits that they desperately needed if they were to stand any chance against

the inevitable challenge from the forces of the crown under Lord Russell who was then at

Honiton awaiting reinforcements.

The mayor and his brethren returned the same answer as before; adding withal, that they

were bad and wicked men, and that they reputed them as enemies, and rebels against God,

their king, and their country; and therefore resolved to hold no further correspondence

with them.

Hereupon the rebels laid siege to the city, as before mentioned, so as to take by force

that which by words they could not obtain; and notwithstanding the answer they received to

their second message, entertained great hopes that they should meet with little resistance,

especially as the greatest part of the citizens were of the same opinion, in matters of

religion, with themselves; and also having with them many friends, who would readily join

them, if they might have liberty to follow their own inclinations. [Hooker, p67-68]

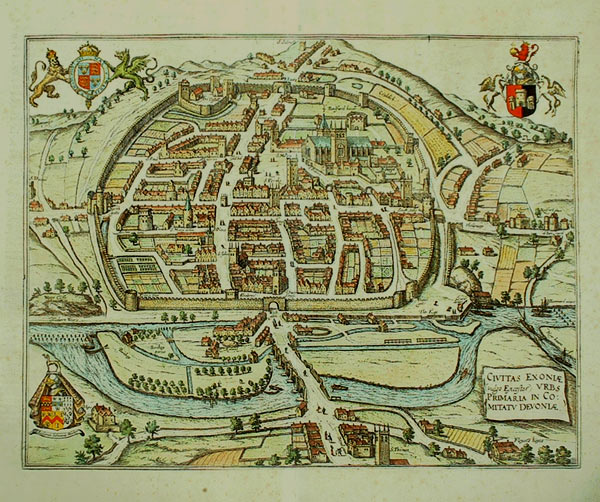

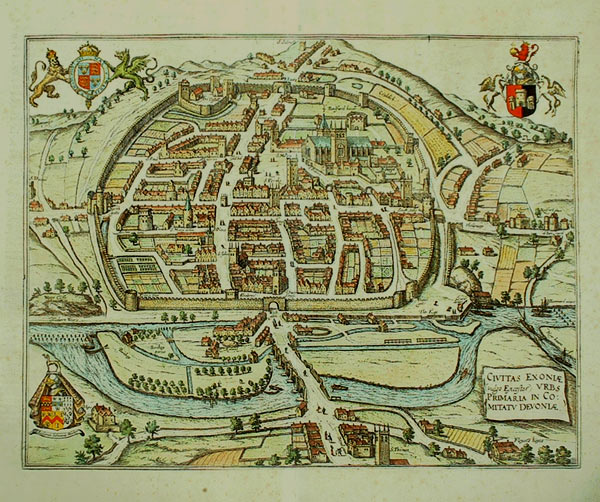

Hooker's 1563 map of the walled city of Exeter viewed from the west. The bridge over the

River Exe carrying the road to the West Gate is seen in the foreground.

The rebel force - some 2000 strong by Hooker's estimate - immediately surrounded the

boundary walls and overran the suburbs; so confident were they of the imminent surrender of

the city that many urged their wives to bring horses with panniers each day in readiness to

enter the city, and measure velvets and silks by the bow, and to load their horses with

plate, money, and other great riches; which they reckon'd only a part of its spoils. [Hooker,

p68]. The rebel army was too small to encircle the city; instead they set up a series of

camps: one outside each of the gates, and some elsewhere, totalling eight in all.

Meanwhile the mayor and his officials began to organize the defence of the city.

For this purpose the city was searched for arms, captains appointed in every ward, soldiers

taken into pay, warders for the day, & watchmen for the night assigned to their several

stations; great pieces of ordnance planted at every gate, and in all convenient places upon

the walls; huge mounts raised in sundry parts of the city, both to save soldiers and

watchmen from the shot of the enemy, and to mount heavy cannon thereon; and every

precaution taken, which the exigency of affairs seemed to render necessary or expedient.

[Hooker, p68-69]

The rebels knocked down several bridges, and felled trees which they used to block roads

leading to the city. Guards were placed at the various entrances; no-one could pass to or

from the city without permission, leaving the citizens to survive on their existing food

stocks. The pipes and conduits providing the city's water supply were dismantled and melted

down to make lead shot.

Having by this means stopped the ordinary course of the markets, and prevented all kinds of

provisions being carried into the city, and penned up the townsmen (so they bragged) as in

a coop or a mew, they

planted their cannon against every gate, and in all such places as they thought would do

most execution

against the city and those who were within it; at the same time burning the gates...

[Hooker, p69]

The defenders used the burning of the gates to their own advantage by extending the fires

inside the walls as far as the hastily erected mounts with cannons on top that were proving

more effective as a means of repelling the rebels than the gates themselves.

A surviving example of Exeter's Tudor past is this 15th century merchant's house at the

bottom of Stepcote Hill which was the main route into the city from the West Gate at this

time.

The rebels had in their midst some Cornish tinners with experience of setting explosive

charges who were put to work in a vain attempt to breach the enclosing walls and gates.

Hooker relates an incident in which an attempt to blow up the West Gate by igniting

gunpowder, pitch, and other combustible matter placed underneath it was thwarted by

the actions of a tinner, one John Newcombe from Teignmouth. Newcombe was within the city on

the night that these explosives were to have been set off. He had some obligation to an

alderman and one-time mayor called William Hurst and he confided in him as to what the rebels

were planning and how it could be prevented. That Stepcote Hill is very steep and leads down

to the West Gate is pertinent.

Understanding the designs of the enemy, he told the said Mr Hurst he would endeavour to

frustrate their scheme; which he effected in this manner: hearing a noise under ground, he

takes a pan of water, and by removing it from place to place, came at length to the very

spot where the miners were working; which he knew for certain by the shaking of the water

in the pan. Immediately on this discovery he set about counter-mining them; which he did to

so good purpose, that in a little time he could and actually did look into their workings.

He then caused every inhabitant who lived in any of the streets that had a fall or descent

into the said West Gate, to place at his fore-door a great tub or tubs filled with water,

and all the wells and tirpits in these streets

to be drawn off, and emptied at one and the same instant that the tubs of water were

overset; which running in great abundance

towards the said gate, was presently conveyed to the place counter-mined, and there entered

the places first mined. The great goodness of God was also further to be observed and

admired upon this occasion; for just at the time that the wells were draining off, there

fell so great a shower of rain, that, (for the time it lasted) the like had not been

remembered for many years. [Hooker, p70-71]

Following this setback they tried various stratagems intended to alarm the citizens such

as threatening to assault the city by scaling the walls using ladders, or attempting to burn

the gates using carts loaded with dry hay which they ignited. The defenders countered this

last ploy resolutely.

both at the South and West Gates their coming being one time perceived, the heavy

cannon

note2 there planted were

charged with great bags of flint stones and hail-shot; and as they approached, the gates

were secretly opened, and the said cannon discharged with so good success, that some of

them were killed, and divers much wounded; by which means those who escaped had but little

stomachs left to come again upon the like enterprises. Nevertheless the citizens, in order

to prevent any other attempts of this kind, caused the gates to be left open. [Hooker, p71]

Snipers were positioned in some of the suburban houses, especially behind the West Gate,

as Stepcote Hill rose so steeply that its houses were visible behind the wall. To stamp this

out the citizens made sorties into these locations to destroy the snipers' houses by fire or

other means.

At other times, parties of the said rebels would hide themselves in such of the houses in

the suburbs as were nearest the walls; and from thence so closely watched the garrets, that

it was with the utmost danger any citizen would venture to look out, as some people had

been killed by them. This occasioned therefore a great part of the suburbs to be set on

fire, and those houses from which the rebels fired into the garrets to be batter'd down, in

order to drive them from their hiding-places. [Hooker, p71-72]

A skilful Breton gunner had been firing into the city with deadly accuracy from his

emplacement on St David's Hill overlooking the North Gate, killing at least one resident.

Emboldened by this success, he put to the rebel commanders his plan to burn the city to the

ground using a barrage of incendiary shot; this was well received and preparations were made

for its execution. That it never came to pass was solely due to this heartfelt appeal against

such a callous action by Robert Welsh, vicar of St Thomas, Exe Island:

For (saith he) do what you can by policy, force, or dint of sword to take the city, I will

join with you, and do my best; but to burn a city, which be hurtful to all men, and good to

no man, I will never consent thereto, but will stand here with all my power against you.

[Hooker, p102]

Welsh, from Penryn in Cornwall, was highly regarded for his physical prowess as well as

his intellect. He paid the ultimate price in the final reckoning for his part in the hanging

of a Protestant spy called Kyngeswell who was caught delivering letters from his master to

Lord Russell in Honiton. This man had been closely watched for some time, and as he was known

for his strongly held reformist views he was the object of much loathing among the Catholic

insurgents. He was tried by Welsh, who acted as a magistrate for the rebels, and was

condemned to death. He was hanged from a tree on Exe Island close to the West Gate.

Given that so many of the besieged were with the rebels in spirit, it is unsurprising that

they should have tried to make contact with those without, and treachery was often suspected.

Special measures were taken by the city's leaders to keep a lid on this as far as was

possible.

There was a certain amount of communication between the rebels and their friends within the

city, secret conferences over the walls, letters smuggled in and out, open parleys in time

of truce. ...A special company of about a hundred citizens made a covenant together,

besides their ordinary duty, to be always about the city day and night to see that no

treachery could be practised: this Hooker regarded as one of the chief means to its

preservation. An attempt to gain the castle by corrupting the soldiers was detected just in

time. [Rowse, p271]

Fortunately for the citizens there were many fresh water springs within the city walls and

loss of the regular external supply didn't cause much inconvenience, but as the siege dragged

on food shortages caused some hardship and weakened the morale of the townspeople.

In the absence of forewarning no emergency stocks of food had been laid in: the disturbed

state of the countryside has rendered any attempts at last minute provisioning impossible.

What there was could not be expected to last very long. Lord Russell's information was

variously that supplies in hand were sufficient for two days or eight. There was a good

store of dried fish, rice, prunes, raisins, and wine in the merchants' warehouses at

reasonable prices, but bread and flour were extremely scarce. Bakers and housewives were

driven to retrieve puffins, or stale pastry and bran which in normal circumstances

were made into feed for horses, swine and poultry; now the mixture was moulded in cloths to

hold it together, and baked. [Cornwall, p106]

Of all the privations that the citizens of Exeter had suffered under siege, hunger was

becoming the hardest to endure. This was articulated vividly by Hooker.

Besides these and sundry other perils and distresses which the city endured, they were now

visited with a calamity more to be dreaded than all the rest, viz. famine, to which none of

the others were in the least degree comparable; for no force is feared, no laws observed,

no magistrates obeyed, nor the ties of common society regarded, where this plague rages.

[Hooker, p83]

With food supplies dwindling the mayor and his brethren were concerned that the common

people would be inclined to yield to the rebels, especially as most sympathised will their

agenda. With this in mind, Blackaller shrewdly introduced food rationing to mitigate the

suffering of the poor.

The probability is that the city would have yielded before this if it had not been for the

able rule of the mayor and his brethren. In this emergency they came up to the trust

reposed in them and adopted wise measures for dealing with the poor people, where the

danger was greatest: first a general rate was imposed for their relief, which was doled out

to them each week; such victuals as there were were issued to them free or at a low price;

if any cattle came near the walls or anything was captured by a skirmish, it was divided

amongst the poor; even the prisoners in gaol had their portions, though they were reduced

to horse-flesh. [Rowse, p275-276]

As the siege dragged on into a second month, a high-profile dispute erupted between two

prominent citizens. John Courtenay, son of Sir William Courtenay of Powderham, who urged that

sorties from the city into the rebel-held areas should cease as they were too dangerous for

the participants. On the other hand, Bernard Duffield, Lord Russell's steward in Exeter, was

adamant that such skirmishes yielded much needed victuals and weaponry and should continue.

The mayor sided with Courtenay, and Duffield was detained. On hearing of this, his daughter

Frances demanded of the mayor that her father be released immediately.

This being refused, she fell into a great rage, and not only uttered many unseemly and

disrespectful speeches, but struck the mayor in the face. [Hooker, p81]

In the confusion that followed, the Common Bell was rung and a rumour spread that

the mayor had been killed or badly beaten. Being summoned by the bell, volunteers wearing

armour hurried to the Guildhall where they saw that the mayor was not harmed. On hearing of

the affront to the mayor's dignity, some became agitated and vowed to haul the young lady

before the mayor to show repentance. Intent on forestalling any further disturbances, the

mayor said he forgave Frances and there was no need for them to fetch her.

On the Sunday before the lifting of the siege a group of Catholics dissenters within the

city attempted to raise a mutiny to no avail.

The malcontents within the city, finding that all their secret practises availed them

nothing; and persuading themselves, that as they were the greatest number, and most of the

poor people began to be faint for lack of food, and quite tired out with being pent up

within the walls of the city, so they would consequently take part with the greater number

against the lesser; they therefore on a Sunday (being but two days before the deliverance

of the city), about eight o'clock in the morning, assembled themselves in companies in

every quarter of the city, having their armour on, and their weapons in their hands.

Meantime those without the walls were in readiness to assist them, if needful. Then

dispersing themselves in every street of the city, they cried out. "Come out these

hereticks, and two-penny book-men

note3; where be they? By God's wounds and blood

note4 we will not be pinned in to serve their

turn. We will go out, and in our neighbours; they be honest, good, and godly men." [Hooker,

p76]

The mutineers' timing was ill-judged as most of their intended audience was either in

church or at home so there was little response apart from a minor disturbance at the South

Gate. The mayor and magistrates had been tipped off about this would-be insurrection, and

they were able to round up the ring-leaders and confine them to their houses.

Following defeat at the hands of Lord Russell and his largely mercenary army in a series

of bloody battles, on August 6th the surviving rebels dispersed and the city was relieved

having endured five weeks under siege.

Compared to many others around the world over the ages, this siege was unexceptional for

its duration, the hardships and suffering of the besieged population (with the exception

of hunger which was becoming increasingly severe by the time the city was liberated), or for the loss of life

or casualties on either side. Nevertheless, given that the majority of the 8000 inhabitants

of Exeter would have been in sympathy with the rebels' cause, it is remarkable that the city

did not succumb within the five weeks of the siege. This must surely be a tribute to the

determined leadership of the mayor John Blackaller and his aldermen. What makes the siege

especially interesting historically is that we have such a vivid eye-witness account of the

unfolding events left to us by that gifted chronicler John Hooker.

The use of the siege as a means of strangling a city into submission still plays its part

in contemporary conflicts, despite the availability of powerful of modern weapons. The

fragment below comes from a report on the uprising in Libya in the New York Times of April

10th 2011. One big difference between Ajdabiya in 2011 and Exeter in 1549 is that in the

former the loyalists are the besiegers, while the rebels are the besieged!

The presence of the loyalists' artillery batteries within range of Ajdabiya has led the

rebels to implore NATO to relieve the city before it falls again, or suffers an extended

siege.

According to Caraman, many of the citizens switched sides at the last minute.

Blackaller then ordered the five great gates of the city to be closed, but not before a

large number of sympathisers had left to join the rebels. [Caraman, p60]

This may well have been a tactical error on their part: by remaining within the city they

would be better placed to organize an uprising against the mayor and his councillors, and

their presence would have meant the meagre food stocks might have run out, leading to

surrender through hunger.

[return]

Caraman says that the 'heavy cannon' deployed on the ramparts inside the gates were relics

from the previous siege of the city in 1497: "

these were guns with a muzzle of 12

inches, with barrels bound together with iron hoops, mounted on a stand of logs. [Caraman,

p76]"

[return]

Two pence was presumably the cost of Cranmer's Book of Common Prayer.

[return]

"God's wounds and blood" is most likely a reference to the Banner of the Five Wounds, the

rebel army's standard.

[return]

Tudor Cornwall by A L Rowse, 2nd Edition, Macmillan, 1969.

The Western Rising 1549: The Prayer Book Rebellion by Philip Caraman, Westcountry

Books, 1994.

Revolt of the Peasantry, 1549 by Julian Cornwall, Routledge & Kegan Paul,

1977.

The image of Exeter's ancient Westgate comes from the Devon County Council "Etched on

Devon's Memory" collection. It is derived from an

1831 engraving by CJG

Sprake.