The middle years of the Victorian era were a period of transition for those living in and

around Dartmoor. After the rich veins of copper to the west of the moor had been exhausted

and the local cloth trade began its steady decline, the industries that had sustained a way

of life over many generations were coming to an end. Nowhere was this more evident than in

the former stannary town of Chagford on the eastern fringes.

With the railway reaching Devon by 1850 there was an increased mobility among the middle

classes across the country, and a new interest in the scenic attraction of the open

expanses of Dartmoor emerged. But for the adventurous visitor the more remote parts of the

moor were inaccessible, and unwary trekkers could all too easily get lost or stuck in the

mires. This created an opportunity for knowledgeable locals to tender their services as

moorland guides. The most renowned of these was the estimable James Perrott of Chagford

whose lifelong experience of the moorland routes was coupled with great skill and

enthusiasm for angling in the locality. William Crossing gives this appraisal of the man in

the chapter on the 19th century 'celebrities' of the moor in his Hundred Years on

Dartmoor:

James Perrott in 1862, age 47

None among the worthies of the Moor was better known to visitors to the district than James

Perrott, of Chagford, who for more than fifty years acted as guide to the tourist over its

wild hills ... Rugged, frank, and of cheery disposition, his sterling worth caused him to

be respected by those who made his acquaintance.

His knowledge of the Moor rendered his conversation exceedingly interesting to those who

found pleasure in that topic - and who that visits Chagford does not? The archaeologist,

the searcher after the picturesque, and the angler have each been indebted to him; there

was not a tor or hill in the northern part of the Moor to which he could not conduct them,

nor a stream in his neighbourhood in which he knew not the pools and the stickles most likely to afford sport. A deft fisherman himself, and

entering keenly into the pleasures of the gentle art, he was always desirous that those who

accompanied him should realise the delight of returning with a well-filled cree. [1,

p82-83]

Perrott was born in 1815 in Coombe near Gidleigh Mill to the west of Chagford to where he

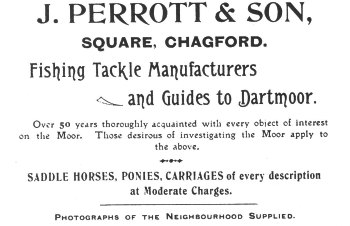

moved at an early age and remained until his death aged 80. As the advertisement shows, he

established a family business in the town providing saddled horses and other horse-drawn

transportation in addition to fishing tackle and guided tours on the moor.

Though he remained in rude health into his last years, by that time the more arduous moorland

treks were conducted by his sons who continued the business after he died. He was buried in the

churchyard of St Michael's in Chagford, his grave adorned by a fine polished granite

memorial stone.

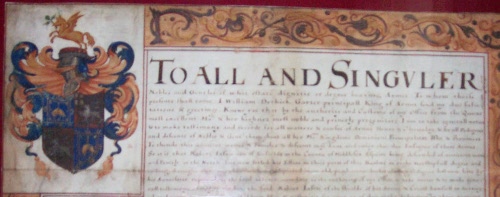

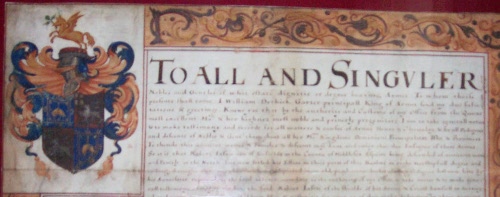

James's family had a noble lineage, having been traced back on his paternal side to the

Perrot who arrived with the Norman conquest, while on the maternal side he was descended

from Sir Robert Jason whose 1588 Grant of Arms was on display in Perrott's Chagford residence.

Sir Robert Jason's coat of arms

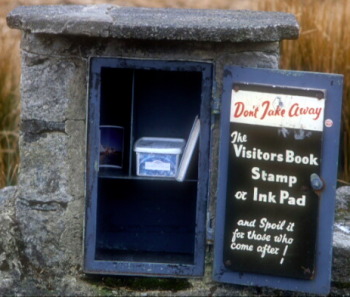

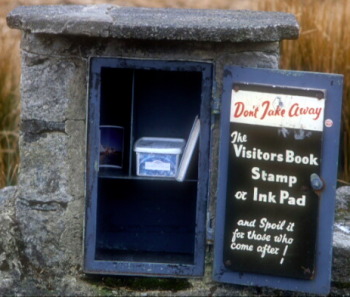

Perrott is best known today for having established the first of what was to become one of

many Dartmoor letterboxes. In 1854 he built a small cairn at Cranmere Pool on which he placed

a bottle where visitors could leave their calling card. A visitor's book was added some time

later note1. Various free-standing

containers have been used for the cards at different times until in 1937, following an appeal

by the Western Morning News, a permanent stone box with a door was built. Since that

time letterboxing as a hobby has spread across the world, and on Dartmoor itself there are

now several thousand letterboxes, often hidden from view.

The arduous eight mile each way round trip from Chagford to Cranmere Pool was a Perrott

speciality. The first stage was on horseback through Fernworthy and then on to Teignhead

Farm, with the rest of the journey being on foot. Many luminaries accompanied Perrott on

this trek over the years, including Charles Dickens, so it is said note2. Nowadays it is much easier to reach Cranmere

by following the military road across the Okehampton firing range southwards, as described

at the bottom of this page.

Charles Kingsley

Perrott became close friends with many well-known West Country writers including novelists

Charles Kingsley and R D Blackmore. He was a long-time acquaintance of the topographer and

poet John Lloyd Warden Page, whose section on Chagford in his Rivers of Devon From Source

to Sea includes this portrayal of Perrott. This work was published in 1893, two years

before Perrott died.

You will meet anglers of every shape and size and pattern, for the Teign is a notable trout

stream, as good Master Perrott will tell you if you look in at the little shop where the

'Dartmoor Guide' is always ready to advise the ambitious tourist. James Perrott is

approaching four-score, but he is, or was when I saw him last, 'as hard as nails'. Nothing

pleases him more than to discourse on matters pedestrian or piscatorial; he knows Dartmoor

from Tavy Cleave to Gidleigh Common, from Princetown to Okehampton Park, and every likely

'stickle' in the Teign from Sittaford Tor to Clifford Bridge. [5, p73]

Perrott is woven into the narrative of Blackmore's Christowell: a Dartmoor tale

in chapter XLIX entitled Cranmere [7, p375] which begins:

"'Tis a terrible rough road, sir," said the famous Mr. Perrott, of Chagford, not then so

widely known as now, but already called 'the Dartmoor guide,' "or rather I should say, no

road at all, after you be past Kestor rocks. But you can't miss the way, without a fog

comes on; if you go according to my directions."

"Thou art very accurate; and I am not a fool. After passing Kestor, I see Watern tor, about

two miles to the west, the one with the hole in it, which thou sayest a man of great

stature can ride through. When I get there, I go south-west, and cross the Walla brook, as

thou hast called it, and then over some rough ground, to another little stream, which is

the head-water of the Taw, and then over a hill, to Cranmere pool."

"You've got it as right as can be, sir; but you can't get to Cranmere very well on

horseback, even now that the bogs be down so. In the winter-time, 'tis a bad job afoot;

without you know the ground as I do. But now, if you go heedful, there isn't much to risk;

for the oldest man never knew the moor to be dried up so. All the black places are safe

enough now ; for the crust is firm on the top of them. And wherever the rushes grow, you

can step freely ; but you must have a care of the bright green moss; for it won't hold a

dog up, let alone a heavy man. But you better let me come with you, sir, though I am not

very fond of Sunday jobs. You may be within a score landyards of Cranmere, and never find

'un after all. I've known a party beat about the hill all day, and come home, and swear

there was no Cranmere."

"Spare me that rubbish, friend; unless thou art afraid, that this queer-looking horse of

thine will break down."

"Charlie break down! Not unless you throw him. Charlie will travel

three-score miles a day, without bit or sup. He is true forest-breed. Only you put him up,

where I told you. But mind you one thing. No weather won't hurt Charlie; but it

may hurt you, sir. And to my mind, the weather will break up, before the day is out The sky

was all red in the east, last night; and the moon lay as flat as a frying-pan. 'Tis eight

o'clock now; you should be there by eleven, allowing for roundabouts, and bad travel; be

back here by three o'clock, if you can sir."

The elderly gentleman, in outward semblance (who had slept last night at the Three-crowns

Inn, and hired Mr. Perrott's best horse for the day), set off, without answer, at a good

round trot; with the murky morning sun behind him, and the heavy dry air slowly waving the

silvery locks, beneath his broad-brimmed hat. "Queer sort of a Quaker, to my opinion," the

shrewd Perrott muttered, as he went back to breakfast; "I have heard say, that they take

no heed of Sunday; but never, till now, that they can put away six rummers of hot brandy and water, in a hour and a

half."

That spirited explorer, Mr. Gaston, who had accomplished this feat last night, and now

looked the soberest of the sober, rode on apace to the bridge across South Teign, and then

through Teigncombe, to the foot of Kestor, where all road failed him, and the wild moor lay

around. Then he pulled off his hot Quaker hat, and hotter wig (both of which he had bought

at Exeter) and hiding them in a deep tuft of bracken, at the foot of a tall rock, which he

would know again, wiped his warm, forehead, and used hot language, concerning the state of

the weather. For the glare of the scorched earth rose, like a blister, and the coppery

clouds compressed it; and the sparkle of splintered and powdered granite, like glistening

needles, pricked the eyes. Mr. Gaston's face came forth in spots, as his mind came out in

tainted language; for which there is no space, but gaps. Then he drew from his pocket a

folded cap, to cover his tawny cropped head from flies, and getting upon Charlie

set forth again.

A long obituary notice appeared in the August 1895 edition of Baily's Magazine of

Sports and Pastimes[8] written by his long-standing fishing partner and friend, F B

Doveton, the poet and author who had previously paid homage to the living Perrott in his book

Fisherman's Fancies. Here are the first two paragraphs of the obituary:

James Perrott, the famous fisherman and Dartmoor guide, who died at Chagford in May last,

in his 81st year, came of ancient lineage, as might be seen from the emblazoned scroll and

coat-of-arms which hung in his moorland home. And he showed it. His was a singularly shrewd

and striking face, with a high, dome-like forehead, and twinkling grey eyes, which betrayed

a keen sense of humour. He was indeed remarkably like the existing portraits of

Shakespeare, save that his eyes were rather smaller and his face longer and thinner. There

was, too, something Shakespearian about the man's breadth of view (considering his rather

narrow sphere) and knowledge of character, which was really remarkable.

James Perrott as an old man

He had guided many men of divers minds, some very great men, across the dreary Devon wild,

and had learnt something from each. Though chained to a remote moorland village, he then

became somewhat of a cosmopolitan in his mental outlook, and his natural shrewdness enabled

him to read some men at a glance. He had picked up during his long life a vast amount of

useful knowledge as well as out-of-the-way lore, antiquarian, folk, natural historic, and

what not. His delightfully quaint speeches, so truly original, and his racy stories will

never be forgotten by those who heard them. But they lose much at second-hand. You want

that keen, humorous, weather-beaten face looking into yours, and the flash of fun in those

quick, grey eyes, to enjoy these tales as they deserve, and that, alas, is impossible now.

The obituary continues for a further 27 paragraphs interlaced with affectionate

reminiscences of shared times. Read the full obituary... »

Perrott is said by Crossing[1, p83] to have "rendered some assistance" to Samuel Rowe

while he was writing A Perambulation of the ancient and Royal Forest of Dartmoor

first published in 1848. But this curious piece from the Exeter Flying Post of September

12th, 1850 shows that Perrott had not set eyes on the book until shortly before this

date.

We have been favoured with the sight of a letter from a gentleman in London who has been

induced to take a journey into Devon by the perusal of the Rev. S. Rowe's Perambulation

of Dartmoor, for the purpose of viewing some of those curious, and in many instances

unique, relics of British antiquity with which that region abounds.

It is gratifying to every Devonian to find that one of the objects sought by the learned author

in his ably executed work has been fully realised. Public attention has been drawn to the

existence of monumental remains of our Celtic forefathers, whereof the great majority of

persons, even in our own county, were profoundly ignorant; and faithful descriptions, from

laborious personal investigation, have been given, so as to satisfy the practised

antiquary, and to furnish a picturesque guide for the less learned tourists. We make an

extract from the letter alluded to:-

"In the two days," says this gentleman, "I visited the Sacred Circle on Gidleigh Common,

the Stone Avenue, the Longstone, and the Tolmen, on the first afternoon, and the second

morning the Bridge at Post Bridge, the Grey Wethers, and Grimspound, at all of which I was

most highly gratified, and quitted with great regret on that afternoon. I gave the book to

James Perrott, the guide, to carry, and he informed me it was wrong, the circle being

incorrect, and the Stone Avenue and the Longstone not being to be found. Nothing daunted, I

proceeded to the circle, where we sat down and identified each stone with the drawing. We

did the same by the Stone Avenue, and warmed by success, Perrott, though fortified by a

moorman as to the non-existence of the Longstone, suddenly suggested he could find it, and

accordingly did so. The obvious connection between the circle, the avenue, and the

longstone, is very striking. It seems that Scorhill and Gidleigh Commons are synonymous,

and that the sacred circle on Gidleigh Common is called by the moormen the

Longstones, and that these circumstances created Perrott's disbelief, who, it

appeared, had never seen the map or book, except in the hands of others, who only asked him

questions, but did not show it to him. He took good care to learn as much as he could, and

the landlady at parting at the Three Crowns, informed us that she intended an

investment in its purchase, understanding from some friend that he could get it for her for

twelve shillings."

It is certainly correct, as the gentleman said, that Scorhill and Gidleigh Commons are one

and the same. The Longstone in a Dartmoor context usually refers to the menhir by

the Shovel Down double stone row, but the entry for Dartmoor in the 11th edition of the

Encyclopaedia Britannica has this line referring to the standing stones of the Scorhill

stone circle as Longstones:

Of the so-called sacred circles the best examples are the "Longstones" on Scorhill Down...

Longstone and menhir are true synonyms, menhir being derived from the Gaelic

maen=stone and hir=long. Hansford Worth would have us differentiate

menhirs by their size and position from stones within rows or circles. This is his

definition of a menhir:

There are on Dartmoor certain standing stones, unwrought, undoubtedly erected by man, and

from their position in association with line or circles of lesser standing stones, or in

isolation, presumably of significance at the time of their erection.

It seems desirable to discriminate between such standing stones, which are marked by their

relative dimensions and special position, and those which form the mass of such remains as

Stone Rows and Stone Circles. And this although the usage of some authors is to speak of

every member of a row or circle as a menhir, whatever its actual size. [Hansford Worth,

p265]

Sometimes a particular menhir is known as The Longstone(or Long Stone), as in the

Shovel Down instance mentioned above. This nomenclature is not specific to Dartmoor; there

is, for example, The Longstone on the Isle of Wight.

The 1896 edition of Rowe's Perambulation was expanded under the editorship of Samuel's nephew J Brooking

Rowe and contains this reference to Perrott in the new section on folklore:

The black dog of the Moor is often seen, and James Perrott, the Chagford guide firmly

believed he had encountered it more than once, and on one occasion he was even bold enough

to attack it, but without any result.

A footnote remarks on Perrott's passing while the book was with the publisher, and adds

this brief tribute:

He was a guide, philosopher, and friend to many, who will regret the loss of so genial and

original a companion. [6, p421]

There is some uncertainty as to when the visitor's book first appeared. The usually

reliable Crossing [2, p480] says a visitors book was added by Mr H P Hearder and Mr H Scott

Tucker of Plymouth in 1905 and quotes the numbers of visitors signing the book for the

first few years following that. Brian Le Messurier on the other hand quotes a private

source describing a trip led by one of Perrott's sons to the Pool by three ladies in 1889

which concludes:

...concealed in the cairn was a tin case, and in the case a little book in which the

adventurous few who reach Cranmere Pool inscribe their names. The trio, of course, added

theirs to the roll call of heroes and heroines of Cranmere and great excitement prevailed

which found vent in hand-shaking all round and in drinking sherry. [3, p236]

See Walking on Dartmoor[4] page 207, for example.

Hundred Years on Dartmoor by William Crossing, 1901; reprinted with new

introduction, David & Charles, 1967.

Guide to Dartmoor by William Crossing, 2nd edition (1912); reprinted with new

introduction, David & Charles, 1965.

Dartmoor A New Study edited by Crispin Gill, David & Charles, 1970. Chapter 8

- Recreation by Brian Le Messurier.

Walking on Dartmoor by John Earle, Cicerone Press, 2nd revised edition 2005.

Worth's Dartmoor by R Hansford Worth, David & Charles, 1967.

1.

2.

I am grateful to James Perrott's great-great-granddaughter Stella for providing

me with the picture of the Grant of Arms to Sir Robert Jason that hung in

Perrott's Chagford home. Stella informs me that the coat of arms consists of

the arms of Jason quartered with those of his wife Susan Lyon.