The two markers on the map of Heywood Wood, bordering the River Taw valley close to Eggesford, point at the earthwork remains of two ancient castles. The motte-and-bailey Heywood Castle can be seen in a clearing towards the northernmost corner of the wood; futher south the smaller Eggesford Castle is hidden amongst the trees.

It does seem odd that two Norman fortifications should be found in such close proximity within the bounds of the wood. Vatchell[1] provides this analysis of how this might have come about.

Heywood Castle is on Forestry Commission land and access is unrestricted. A wide footpath leads from the public car-park indicated by a blue P marker on the map. The car-park is just off the road in the south-west corner of the wood, beyond the Heywood sign.

The National Heritage Pastscape record for Heywood Castle describes it as:

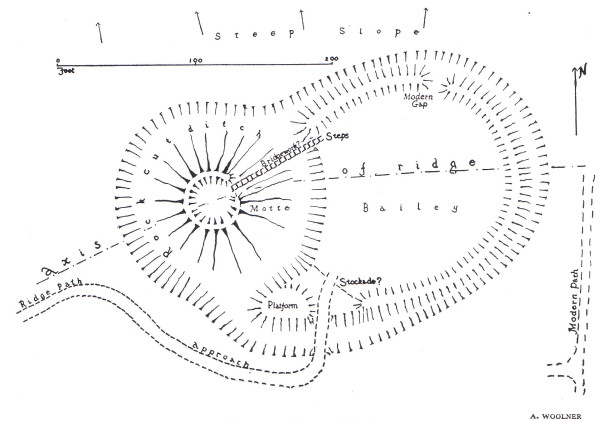

This sketch plan of the castle appears in Vatchell's 1963 TDA paper[1]. The wooden steps on the south side of the motte seen in this 2009 photo are not marked on the plan, suggesting they are of recent origin. The ditch surrounding the motte is visible in the foreground.

When I visited the site in July 2009, the bailey was covered with a thick blanket of bracken and wild flowers, obscuring its outline. Looking down at it from the top of the motte, the gently rolling hills of rural Mid-Devon stretch out in the distance.

There is no sign of masonry having been used to bolster the defences of either the motte or the bailey, nor, according to Vatchell, are there any signs of the holes or trenches which are the usual indications that masonry has been robbed from the site. It may be concluded that any fortifications, such as a surrounding palisade, were constructed from timber alone.

No, this isn't an artist's impression of what Heywood Castle might have looked like in Norman times. This drawing from the archives of the Devon Record Office is an outline plan dating from 1804 for a proposed folly to be built on top of the motte. According to the annotations there was to be a tower with a tearoom and two cottages behind the wall. Thankfully, for reasons unknown this crazy scheme never materialised.

The Heywood estate was then owned by the Hon. Newton Fellowes, who had inherited it from his maternal uncle Henry Arthur Fellowes. It had been held under trust by his mother Urania Wallop, wife of the 2nd Earl of Portsmouth, until Newton's coming of age, at which time Newton took the name and arms of Fellowes. By all accounts Newton seems to have been a level-headed chap, so it is somewhat surprising that he should come up with this hare-brained idea. Perhaps it was cooked up by his eccentric elder brother John who had become the 3rd Earl of Portsmouth on the death of their father in 1797?

Newton Fellowes made two separate attempts over the next twenty years to obtain judicial confirmation of his brother's insanity so he could inherit John's title and his substantial Hampshire estate. Or was it, as the more charitable contemporaneous accounts would have us believe, intended to spare his brother further humiliation at the hands of his sadistic second wife, Mary Anne Hanson?note 2 In the first commission of lunacy taken out by Newton in 1814 the Lord Chancellor ruled against him. Undeterred, he tried again nine years later.

In February 1823 the inquisition into the 3rd Earl's sanity was held before an appointed body of commissioners and a 23 strong jury in the Great Hall of Freemasons' Tavern, Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields. At the end of a trial lasting 17 days costing Fellowes as much as £25,000 the jury reached the unanimous verdict that John Charles Wallop had been "of unsound mind and condition, and incapable of managing himself and his affairs" since before his second marriage. Five years later that marriage was annulled on the direction of the Lord Chancellor leaving his daughter, the only issue from that union, illegitimate and thus disinherited. His first marriage had been childless.

Finally Newton Fellowes had secured his inheritance. But it was a long time coming: the 3rd Earl survived until 1853, his eighty-sixth year. On the passing of his brother, Newton took ownership of the Hurstbourne estate and became the 4th Earl of Portsmouth, a title he was to hold for barely six months before he departed this earth too.