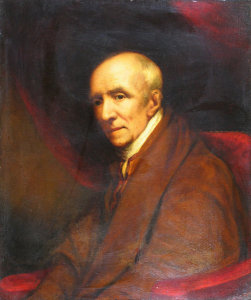

James Northcote was one of a number of prominent painters of the 18th century who hailed from the Plymouth area of Devon, the most notable of whom was Sir Joshua Reynolds, the founder and first president of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Today Northcote is chiefly admired for his portraits, though his paintings of animals found favour in his lifetime. In his later years he devoted an increasing amount of time to history paintings, including some scenes from Shakespeare's history plays which were exhibited in Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery.

Northcote is renowned also for his writing, penning the first full biography of Reynolds in 1813, and later a Life of Titian, as well as a book of fables lavishly illustrated by woodcuts crafted from his own designs. He had trenchant and outspoken views on his fellow artists and other famous figures of the day; these opinions were expressed publicly in William Hazlitt's Conversations with Northcote that appeared in book form a year before Northcote's death in 1831. A prolific artist, Northcote was credited with around 2000 works, and by living frugally in his London house for the last fifty years of his life he died a wealthy man.

Born in Plymouth on October 22nd 1746, little is known of Northcote's early years, save that like the illustrious Reynolds before him, he was educated at Plympton Grammar School. Remarkably for such a small school, two more famous English painters of this period were former pupils: Benjamin Haydon who become head boy in 1801, and Sir Charles Lock Eastlake (1793-1865), a one time president of the Royal Academy. The etching of the school reproduced below dates from 1820.

Founded in 1658 by a bequest from one Elize Hele, it was originally called Hele's School and was highly regarded in Reynolds' day. Though modest in size by modern standards, the building impressed Samuel Rowe who wrote in 1821:

By the mid 19th century the school had entered a period of decline after a failed attempt to replace the classical curriculum with more commercial courses. With the number of pupils dwindling and the building falling into disrepair, the school was closed down following the introduction of state control for secondary education in 1902 and didn't reopen until 1921.

The Grammar School made no lasting impression on Northcote and goes unmentioned in his memoirs; indeed he criticises his father for leaving him disadvantaged by neglecting his education:

On leaving school Northcote was apprenticed to his father, a humble watchmaker who was opposed to his son becoming a professional painter. Frustrated in his desire to become an artist, and feeling like a caged bird, he vowed to make a break from his father: "..tired of my present mode of life, I decided rather to throw myself on the wide world.".

In the summer of 1771 he and his elder brother left Plymouth for London telling their father that they would return within a fortnight. With only 10 guineas in their pocket, they decided to travel a considerable part of the journey on foot. Northcote relates how, arriving dishevelled and weary at Woodyates Inn between Blandford and Salisbury, they were refused a bed for the night and were obliged to sleep in the hayloft with the grooms and post-boys.

Unknown to either his brother or father, James had in his pocket two other valuable items: letters of introduction to Sir Joshua Reynolds. One was from Mr Henry Tolcher, a senior Alderman from the city of Plymouth, who had long been convinced of James's artistic talent. To the considerable irritation of his friend Samuel Northcote (James's father), Tolcher frequently counselled him to send his son to London to study painting. The second letter was from Dr John Mudge, an eminent Plymouth surgeon who was a personal friend of Reynolds.

The day after their arrival in London, Northcote lost no time in delivering his letters to Reynolds.

James was given the freedom to spend his days copying pictures from Reynold's collection, and it wasn't long before he was invited to come and live in the house and assist the master on a permanent basis. Northcote joined two other younger assistants making copies and painting the draperies on portraits at Reynolds' bidding. During his time with Reynolds he had occasion to meet with distinguished men of letters such as Oliver Goldsmith and Samuel Johnson, and the renowned Shakespearean actor David Garrick, who were regular visitors to Reynolds' house.

After more than four years of this essentially menial work, Northote decided that his artistic skills were not progressing as they should, and it was time to part company with Reynolds which he did on amicable terms.

He left the service of Reynolds in 1775, travelling to Portsmouth the following year before returning to Devon. He managed to save enough from portrait commissions to realise his ambition of making an extended visit to Italy:

Aspiring artists from across Europe congregated in Italy at the time, and Northcote encountered several individuals who would become eminent later in life. Among these was the painter Henry Fuseli from Zurich, an early exponent of the romantic movement who later settled permanently in London. Like Northcote, Fuseli lived to a ripe old age, and the pair were friends and rivals on the London scene for another half century. They both had sharp tongues, and it was said that they watched each other like game cocks before a spurring match.

On his return to England three years later, after a short visit to Devon, Northcote moved back to London where he remained for the rest of his long life, dying aged eight-five with his faculties unimpaired until the very end.

On returning to London from his sojourn in Italy, Northcote was hoping to set himself up as a portrait painter. But, lacking a patron and experiencing considerable competition from among others the newly arrived and highly regarded Cornishman John Opie, he turned of necessity to painting "small historical and fancy subjects from the most popular authors of the day, as such subjects are sure of sale amongst the minor print-dealers, being done in a short time, and for a small price. 2, p200"

In Northcote's day the sale of prints was an important source of extra income for an aspiring professional painter; it was important to work in partnership with a competent engraver and to paint images that would appeal to the public.

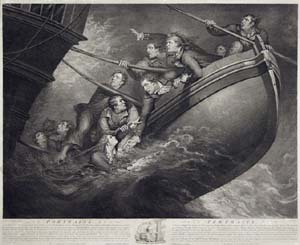

One popular print of a Northcote painting from this period depicted a recent shipwreck: that of Captain Englefield and eleven of his crew who survived in a small boat after the sinking of the man-of-war Centaur on return from Jamaica. The print of this scene by Thomas Gaugain is shown alongside. Gaugain was a French engraver and publisher who collaborated with Northcote on many occasions, and was his engraver of choice.

Aiming to capitalise on a revival of interest in Shakespeare in the late 18th century, in 1786 the publisher John Boydell and his nephew Josiah embarked on an ambitious scheme to promote historical painting in London. The Boydells' scheme had three elements: a purpose-built gallery to exhibit specially commissioned paintings of scenes from Shakespeare by leading contemporary artists, an illustrated edition of Shakespeare's plays, and a folio of prints from the gallery items.

Northcote was commissioned to contribute canvases to the Boydell collection from its inception, and later claimed credit for inspiring the Boydells to embark on their project:

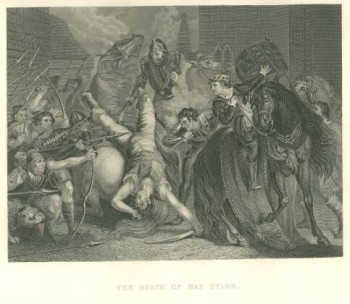

An intriguing connection between the 'Murder of the Princes' and his 'Death of Wat Tyler'[note 2], a large canvas also painted for Alderman Boydell who was Lord Mayor of London by this time, is revealed in this anecdote from Northcote's memoirs:

By now Northcote had achieved the recognition he sought. He was elected associate of the Royal Academy in 1786, and accorded full membership the following spring. Notwithstanding his new found status, he was chided as a penny-pincher by his detractors; following the acclaim accorded to his 'Death of Wat Tyler' painting at the 1787 Academy Exhibition, Fuseli remarked with his customary sarcasm:

After initial success, especially with the gallery of paintings in Pall Mall, the Boydell project eventually foundered partly due to the uneven quality of the material, especially the engravings for the folio. By the middle of the 1790s the volume of subscriptions for the folio was in decline, and poor record-keeping of the existing subscriptions was creating further problems. Eventually the Boydells became insolvent and the Gallery and its contents were sold off in a lottery. Northcote later made this scathing comment on the efforts of the lesser known contributors:

Northcote first began to write for publication in 1807 when he contributed pieces for various periodicals, and in 1809 he wrote a short memoir on Sir Joshua for John Britton's series, Fine Arts of the British School. The first edition of his Life of Reynolds5 appeared in 1813. This version contained a number of Northcote's essays that had first seen light of day in The Artist magazine which were dropped in the second edition.

His Life was not merely a life of Reynolds but also a hotchpotch of opinions and reminiscences taken directly from his hand-written volume of memoirs that formed the basis of Gwynn's Memorials2, discrediting the rumours circulating at the time that Northcote has simply signed a biography written by someone else. Hazlitt recounts that a certain Mr Laird has assisted Northcote in readying the book for publication, but it was otherwise in his own hand. The book has had its critics but was a treasure-trove of anecdotes from the last surviving member of Reynolds' inner circle.

Essayist William Hazlitt had a long friendship with Northcott, his senior by more than thirty years, and held him in high regard. Hazlitt published a sequence of their conversations in the New Monthly Magazine which were eventually published in book form as Conversations with Northcote6. In the following extract from one of Hazlitt's essays he expounds on why he found Northcote such agreeable company:

Hazlitt collaborated with Northcote on two other publications, the Life of Titian and Northcote's Fables, but this did little to enhance the writing in this last work which was the old man's last and most cherished venture. According to Gwynn (referring to the fables) neither Hazlitt or anyone else could have redeemed them from dullness.2, p25

A second edition of the Fables was published posthumously financed by a clause in his will setting aside between £1000 and £1400 explicitly for this.