The ancient Oxenham family dwelt in South Tawton on the north-eastern fringe of Dartmoor from at least the time of Henry III, occupying a manor of the same name. The most notable exemplar was Captain John Oxenham, a companion of Sir Francis Drake, who accompanied him on his voyage to Nombre de Dios in 1572. Later he became the first Briton to set sail in the Pacific. He met an untimely death after being captured by Spanish soldiers who took him to Lima in Peru where he was hanged for piracy in 1580.

An anonymous twenty page pamphlet appeared in London in 1642 with a title beginning A True Relation of an Apparition describing a peculiar circumstance that presaged the deaths in 1635 of four members of the Oxenham family living in the Devon village of Seal (later Zeal) Monachorum, a phenomenon subsequently referred to as the Oxenham omen.

The Lysons brothers' volume of the Magna Britannia on Devonshire [2] from 1822 questions the reliability of the Apparition tract, partly because there was no trace of the Oxenham family "either in the register, church, or church-yard of Zeal Monachorum". This has been elaborated on by later commentators including Richard Cotton[1] whose paper quotes a substantial part of the tract and includes material relating to later incidents of the omen. Sabine Baring-Gould[3] writing a quarter-century later covers similar ground but does a pretty good hatchet job, more or less dismissing the phenomenon as a myth.

W G Hoskins[8] took issue with Baring-Gould and (by implication) the Lysons over the Oxenham family's connection with Zeal Monachorum:

The Court of Wards records showed that James Oxenham the younger had accumulated a substantial estate consisting of 751 acres spread across nine Devon parishes, together with houses in Barstaple, North Tawton and Zeal Monachorum.

Recent evidence collated by Ann Adams[4] from wills and churchwarden's accounts confirms that a branch of the Oxenhams had moved to Baron's Wood (formerly Baronswood) in the parish of Zeal Monachorum from their family seat near South Tawton by 1630, some of whom died there during that decade. While many details given in the Apparition may be erroneous or fictitious, at least one, and possibly a second, of those whose deaths it related appear to have lived and died in Zeal Monachorum around the time the tract claimed they did.

Baron's Wood Farm, now an equestrian centre, can be seen on the map about 1.5 miles to the west of Zeal Monachorum.

There are several reasons for doubting the truthfulness of the account of events contained in the Apparition. First of all, don't believe everything you read in an old pamphlet. Undoubtedly the aim of the author would have been to sell as many copies as possible, to be achieved in this case by dressing up what was probably just hearsay into a sequence of similar supernatural occurrences. To enhance the credibility of the narrative, the tract adopts the familiar device of naming a pair of worthy witnesses who testified to seeing the white-breasted bird appear before each of the four Oxenham deaths. A total of six witnesses are mentioned of which only two have been identified from parish registers subsequently, leading Baring-Gould to suggest that, as in other such pamphlets, the witness statements may have been fabricated:

In a bid to make their testimony appear genuine, the pamphlet says the witnesses to the first apparition confirmed their observations before the minister of the parish who had been appointed by Joseph Hall, Bishop of Exeter, to inquire into the matter:

In contrast to Baring-Gould, Cotton appeared predisposed to accept the witness statements as genuine, given their supposed endorsement by a man of the cloth:

In its portrayal of the victims, the tract gives their familial inter-relationships in an unsatisfactory and inconsistent way, and it contains other factual errors.

The title refers to the "godly lives, and deaths of some of the children of James Oxenham", yet the second death is said to be of Thomazine, the wife of James Oxenham the younger, the third death that of Rebeccah, the eight year old sister of the said Thomazine, and the fourth death that of the infant Thomazine, child of James Oxenham the younger. In other words, only the first victim was the child of James Oxenham senior.

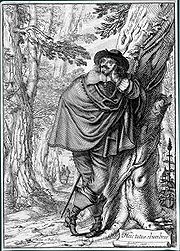

The text below the image representing Rebeccah in the frontispiece refers to her as Rebeccah Oxenham. Why does she have this maiden name if she is the unmarried sister of Thomazine? Are we to assume she is an Oxenham in blood as Cotton doesnote1, or was she given this name for the sake of convenience because the writer did not know the maiden name of Thomazine?

The stated location is only partially correct: Adams has shown that James Oxenham the younger and his family moved to Zeal Monachorum around 1630. But James Oxenham senior remained in Oxenham Manor by South Tawton which is where his son John died in 1635, albeit in May according to the parish register, not September 5th as the pamphlet would have us believe.

Elizabeth and his father, James senior, are referred to in this extract from James's will. In the concluding paragraph (not shown) the residue is bequeathed to his wife whose name is given as Anna in the will.

Adams mentions that the James Oxenham of Zeal Monachorum was the son of James and Elizabeth Oxenham, and it is known from the South Tawton register that they were married there in 1608. Thomasine is assumed to have died before James junior because she was not mentioned in the latter's will. From the parish records we know that Anne survived her husband James.

Another item in Adams's book which may be significant is the following entry from the churchwardens' accounts listing burials within the St Peter's Church in Zeal Monachorum:

To summarise, the depiction of each member of the Oxenham family mentioned in the pamphlet is inaccurate in some respect:

A John Oxenham did die in 1635, but he lived in South Tawton, not Zeal Monachorum.

The wife of James Oxenham the younger of Zeal Monachorum was not Thomasine, but Anne, and she did not die before James himself who, according to the churchwardens' accounts, was buried in the church in 1636.

It is mentioned by Adams that Anne widow of James Oxenham junior became the second highest rate payer in the village, and if the Elsdens were poor, it is quite likely that James would offer to pay for the burial of Rebecca if she were the sister of his wife. Adams doesn't give Anne's maiden name; it may have been Elsden - if anyone can provide me with this information I would be most grateful. Whether of not she was Anne's sister, it is plausible that Rebeccah Oxenham, the third victim according to the pamphlet, was actually Rebecca[h] Elsden.

Thomasine, the infant daughter of James Oxenham the younger died in Zeal Monachorum, but not until 1636, the year of her birth.

The tract also mentions an earlier alleged instance of the apparition at the death of Grace Oxenham, the grandmother of John Oxenham, 17 years before. The pamphleteer then seeks to silence doubters by noting that four Oxenhams who became ill and then recovered fully did not see the apparition.

Cotton provides corroboration from the South Tawton register of deaths that Grace did die in 1618:

Before leaving the story as it relates to Zeal Monachorum, interestingly Cotton mentions that the deaths of the victims could not to be verified in the parish register because part of a page that might have contained these 1635 entries had been removed. My intention is to confirm this by examining the register. Here are Cotton's observations on the matter:

John Prince in his Worthies of Devon refers to this curious phenomenon affecting the Oxenhams, mentioning the version of events recounted by James Howell in his familiar letters:

James Howell was a highly regarded writer and historian who moved in royal circles and was appointed clerk to the Privy Council by King Charles I in 1642, a position he was unable to take up due to the outbreak of civil war. In 1643 he was ordered to be detained in Fleet Prison by a Committee of Parliament for his Royalist sympathies (or perhaps for his indebtednessnote2), where he remained until 1651.

Here is the full text of the relevant letter:

Whatever the literary merit of Howell's letters, it is known that many of them were written expressly for publication in order to pay for his 'necessities' while he was in the Fleet, and were never sent to the named recipient. Also, in all editions of his familiar letters after the first (which appeared three years after the tract), arbitrary dates were appended, so we can disregard the chronological inconsistency of this letter supposedly being written three years before the deaths of the Oxenhams referred to in it. Of more concern is the disparity between the names and familial connections of the Oxenhams mentioned in the tract and those Howell recalled as being inscribed on the monument.

Did Howell ever see such a monument, or was the letter based on his vague recollections of the pamphlet which referred to the existence of such a monument in the following passage?

Turning to my two main sources for an answer to this question, surprisingly they came to opposite conclusions!

Given that no trace of such a monument as ever been found, I am inclined to agree with Baring-Gould when he suggested:

Cotton reasoned perversely that the discrepancies in the details between Howell's letter and the tract showed that he was unacquainted with the latter, and that he really did see the monument:

As to why there is no record of the monument since Howell's sighting of it, Cotton believed it was unlikely to have been destroyed by an over-zealous 19th century church restorer; more likely it never reached Devon. He gave this alternative cause for its disappearance:

Whether a white (or white-breasted) bird did appear at the deathbed of an Oxenham we shall never know for certain, but the superstitious mind of the 17th century would readily accept this bird-like apparition as a supernatural event. However, the following physical explanation was proposed later. There is one white-breasted bird native to the region: the ring ouzel, colloquially known as the mountain blackbird, a summer migrant of the thrush family very much at home in the rocky terrain of Dartmoor. Mr W Burt in his notes to Carrington's Dartmoor[5] suggests that a chance visit by this bird may have given rise to the tradition:

Although this explanation can't be ruled out, it appears most unlikely because the ring ouzel is known to be very shy of human contact; nor is there any reason to suppose it would be attracted by a light.

Moreover, the choice of this bird conflicts with the more recent instances of the tradition in which it was said that a white bird had appeared rather than a white-breasted bird.