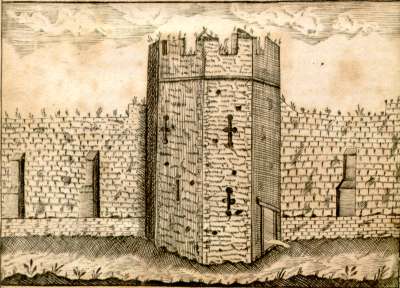

In fifteenth century England many of the most prestigious cities in the kingdom were completely enclosed by fortified walls, with access controlled by heavily guarded gatehouses. The cathedral city of Exeter was one, having been fortified since Roman times. The crumbling remains of the Roman walls and earthworks were replaced by the Saxon King Athelstan in about 920AD with thick walls of hewn stone, incorporating defensive towers. Some time later, access to and from the city was restricted to the four gates at each point of the compass.

Well maintained city walls were a striking visual manifestation of a city's importance and prosperity. They also provided peace of mind to the inhabitants in what was a lawless age. Apart from the threat of invasion by foreign raiders and local rebellions, undefended towns were vulnerable to attack by robbers and outlaws entering from outside, particularly at night.

A walled city was a prime target for a rebel army; its conquest would give the victors a strategic regional stronghold, or at the very least a refuge of last resort should they be routed in subsequent hostilities.

The year 1497 was a tumultuous one for Exeter which faced sieges and incursions from Cornish rebel armies on two separate occasions.

It was Benjamin Franklin who coined the old maxim that in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes. In extreme circumstances these certainties sometimes collide: on several occasions when taxes were imposed disproportionately on the poor of England they rose up, risking death through civil insurrection. So it was in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, precipitated by heavy-handed attempts to enforce a deeply unpopular universal poll tax, and again in Cornwall in June of 1497 in the reign of King Henry VII.

Historically taxes have been exacted for one purpose only: to finance wars, and 1497 was no exception. Henry VII was keen to top up his war chest to support intended incursions into Scotland in response to raids on northern England in the autumn of 1496 by James IV with the support of Perkin Warbeck, pretender to the English throne. He asked parliament to sanction subsidies in addition to the traditional fifteenths and tenths. These were deemed unjust and excessive, especially in areas remote from Scotland. The Cornish tin miners were incensed by Henry VII's decision to impose these new taxes and suspend the Stannary Parliament in 1496. The privileges of the Stannary Parliament (covering the stannaries of Dartmoor in Devon in addition to the Cornish stannaries) had been given to Cornwall by Edward III when he created the Duchy of Cornwall in 1337. The parliament's jurisdiction covered all civil matters, but not criminal offences relating to land, life or limb.

The first stirrings of dissent arose in the parish of St Keverne in the Lizard peninsula under the forceful leadership of one Michael Joseph, a blacksmith (an Gof in Cornish). This followed resentment against the actions of Sir John Oby, provost of Glasney College in Penryn, the tax collector for that area.

As support for a rebellion against these taxes grew, a second leader emerged: Thomas Flamank, a persuasive lawyer from Bodmin who was the son and heir of Richard Flamank, one of the commissioners for the collection of the subsidy. Thomas argued that the extra monies should be raised by a scutage levy on the nobility of the northernmost counties. His anger was vented at Cardinal Morton and Sir Reginald Bray who were the king's counsellors held responsible for these measures, rather than at the king himself, and he urged his followers to march peacefully to London to petition against these unfair subsidies.

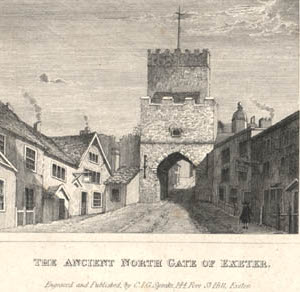

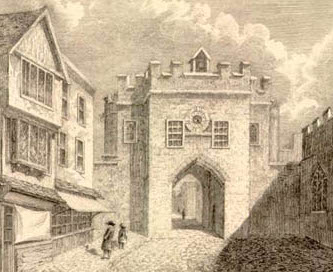

In June of 1497 a rudimentarily armed band of several thousand men assembled at Bodmin. Under the leadership of Joseph and Flamank they marched towards Launceston and the Devon border on route to Exeter, hoping to file peacefully through the city to elicit support for their cause. On arrival at the city gate they were denied entry and threatened to start a siege. The mayor John Atwill was completely unprepared for a rising from the west. Lacking a militia to defend his city, he turned to the only rapid response force available at the time: Edward Courtenay, the earl of Devon, and the other loyal supporters of the crown among the local nobility.

The Exeter historian John Hooker, writing 70-80 years after these events, records that the mayor received a lukewarm response, with most of the local gentry unwilling to provide assistance at such short notice, though there is evidence that the earl himself was up for it: the Receivers' Accounts for Exeter in 1497 included an entry for the costs of "men riding with the earl of Devon against Michael Joseph and his fellow rebels".

The rebel leaders had no wish to remain at Exeter for too long, so a compromise was agreed upon without bloodshed or a prolonged siege. Flamank and Joseph together with their attendants would pass through the city while the rest of the army marched round the walls to meet with them at the East Gate. In Hooker's account the small group passed through the city peacefully apart from shouting angry threats at the mayor as they passed him standing outside the Guildhall.

The rebel army marched on to Taunton, where, in the only violent incident of their long journey, they exacted brutal revenge on Sir John Oby who was slaughtered and his body dismembered. They had been gaining supporters along the way, and at Wells they were greatly encouraged when a disaffected nobleman, Lord Audley, joined the throng, becoming their third leader. By the time they reached the outskirts of London their numbers had swollen to as many an 15,000.

They had hoped to enlist the support of the men of Kent, known for their strong tradition of engagement in popular risings, but this was not to be. They set up camp at Blackheath to the south-west of the capital where on June 17th they were engaged by the King's army under Lord Daubeney. The rebels were poorly armed, lacking horse or artillery, and were by now surrounded on all sides. They were no match for the regular forces and as many as 200 were slain before the remainder dispersed. Flamank and Audley were captured on the battlefield, while Joseph took sanctuary in a church before finally surrendering.

On June 26th the three rebel leaders were condemned to death for treason; next day Joseph and Flamank were drawn through the streets from the Tower to Tyburn to be hanged. These two traitors were subjected to the cruelest sanctionable punishment: a short drop to avoid immediate death, followed by disembowelling and quartering. Audley, being of noble blood, faced the lesser punishment of beheading. The heads of all three were displayed on pike-staffs on London Bridge in keeping with the prevailing custom. Joseph was defiant to the end, declaring that "he should have a name perpetual and a fame permanent and immortal". An Gof's martyrdom still resonates with Cornish nationalists. On the 500th anniversary of the rebellion in 1997 a statue of Joseph and Flamank was unveiled in St Keverne, and a march to London retracing the journey of the rebel army was organised under the banner Keskerdh Kernow 500.

The shadow of Perkin Warbeck hung over the first Cornish rebellion of 1497. The tax raising measures of Henry VII that provoked it were a direct response to King James IV of Scotland's belligerent actions in pursuit of Warbeck's agenda to challenge the legitimacy of the English monarch. Perkin Warbeck, whose real identity was Piers Osbeck from Tournai in the Netherlands, first came to public notice in Ireland in 1491 at the age of 17. Perhaps because of his fine clothes and courtly manner he was able to pass himself off as Richard, Duke of York, one of the two "Princes in the Tower" allegedly murdered by Richard III in 1483.

He was received with open arms in Scotland in 1495, where King James IV recognised the young pretender's Yorkist credentials and offered him the hand of his cousin Lady Katherine Gordon in marriage. In 1497 news reached Warbeck of the Cornish rising, and by this time his presence on Scottish soil was becoming an embarrassment to James, so he was happy to assist Warbeck in his plans to capitalize on the discontent of the Cornish.

Despite the rebels' crushing defeat on Blackheath common, the English monarch had decided against making the long westward journey to reassert the loyalty of his Cornish subjects, fearing it might provoke further anger. This provided Warbeck with a chance to foment further rebellion in the county. Early in June 1497 he set sail from Scotland in a small vessel called the The Cuckoo provided by the Scottish king, accompanied by his wife and about 30 men. They broke the journey for a month in Ireland, arriving in Cork in late July. Bolstered by some reinforcements, they set out on the last leg of the voyage to Cornwall in three boats, landing in Whitesand Bay near Land's End on September 7th with a couple of hundred men in all. This despite the loyal Mayor of Waterford having informed King Henry of Warbeck's intentions, whereupon the king ordered the mayor to send ships to intercept their vessels to no avail.

They marched eastwards through Cornwall after leaving Katherine in the safe hands of the priests on St Michael's Mount. On reaching Bodmin Perkin proclaimed himself King Richard IV and within a few days his army had swollen to more than 3000. They were drawn mainly from the lower orders, though there is evidence that a significant number of the lesser gentry and the yeoman class of the county joined the rebels [Rowse, p130].

Warbeck was advised by a council of three who decided on an immediate assault on Exeter. There was no better way to raise the spirits of a rebel army than the adrenaline rush from the conquest and plunder of a prosperous town, with the prospect of disaffected locals joining the mayhem then rallying to your cause.

First-hand accounts of Perkin Warbeck's attempt to besiege the city come from two letters sent by the earl of Devon to Henry VII who was at Woodstock in Oxfordshire. The first of these is lost but its contents were conveyed to the Bishop of Bath and Wells by the king; it reported that Perkin's army assembled to the north of Exeter at 1pm on Sunday September 17th. He then called in vain on the earl to surrender the city, and the siege began with attempts to breach the North Gate and the East Gate. The earl's letter went on to say that the city was so well defended that Perkin lost 'above three or four hundred men of his company' and the rebels were repelled. The earl's second letter tells of another assault on both these gates the next day, again without success, and that after being fired on by the guns of the defenders, Perkin pleaded to be allowed to assemble his followers without hindrance before departing peacefully. The earl acceded to this and they duly departed for Cullompton.

This is the relevant section of the earl's second letter to the king dispatched from Exeter on September 18th:

The earl of Devon's letters confirm the chronology of the siege but there is no mention of the rebel tactics and how these were countered. It was left to various chroniclers to furnish an embroidered version of events including the attempts to burn the gates and scale the walls. Among these was the Italian historian Polydore Vergil writing some fifteen years later who describes how the defenders used fire to fight fire, a recurrent theme in the chroniclers' narratives:

The most substantial account of these events appears in the Gleanings[3], derived largely from the manuscripts of the 16th century Exeter historian John Hooker note1:

Undoubtedly the rebels suffered many more casualties than the better armed defenders, though the earl's estimate of enemy losses on the first day may be overblown. It does seem likely that the East Gate was breached: the Receiver's Accounts for 1497 include numerous entries for the cost of materials and labour incurred for its repair note3. But, having been beaten back and fired on by artillery for the first time on the second day of the siege, Perkin and his followers realised the game was up. They were left with no choice but to depart quietly with their hopes dashed and their morale shattered.

As for the citizens of Exeter and its defenders, this victory was a lasting source of civic pride.

When Perkin's army found out that he had fled most of them dispersed. Meanwhile the king and his forces were on route from Woodstock to Taunton, arriving on October 4th to be joined by his chamberlain Lord Daubeney and his militia. Perkin was soon traced to Beaulieu by a unit of Henry's troops, and the pretender decided to throw himself at the king's mercy. He was taken to Taunton and accompanied the king as a prisoner on the triumphal march to Exeter where the monarch was welcomed with jubilation.

In the aftermath of this rebellion Henry VII had decided to come in person to show gratitude to those who had defended the loyal city, and to supervise the restoration of order in the West Country. He remained for nearly a month and the city did its very best to entertain him. He lodged at the house of the cathedral treasurer that used to stand between the north tower of the cathedral and the street that now runs down to Southernhay.

Perkin's wife Katherine was fetched from St Michael's Mount. The king took a shine to her, and she was accepted into his court under the wing of the queen and eventually remarried. While she was in Exeter, Perkin was humiliated by being forced to repeat his confession in front of her which included these words:

Those remaining in the city who had taken part in the rebellion had been rounded up and were paraded each day in the cathedral close past the king's residence with halters around their necks (symbolizing the hangman's noose) in a mass plea for the king's mercy. Eight trees were felled and a large new window was opened for the king to get a good view of the proceedings. When the appointed day came, the king proclaimed that he would punish the ring-leaders (by execution) but spare the lives of the majority.

Those spared shouted "God Save the King!" and threw down their halters.

Commissioners were appointed to impose hefty fines on those wealthy individuals and boroughs in the West Country that were deemed to have given succour to the rebels in each of the two risings, if only by giving them hospitality during their onward marches.

Eventually Perkin was taken to London and paraded through the streets before being held at court from where he escaped but was soon recaptured. He was then made to suffer further humiliation in the pillory at Westminster before being transferred to the Tower. Perhaps with some encouragement, he escaped once more, this time in the company of his fellow prisoner the earl of Warwick, the last of the Plantagenets. This give the king his opportunity to be rid of them both. They were recaptured and tried for treason before being executed at Tyburn in the same barbaric manner as Joseph and Flamank were for their role in instigating the first Cornish rebellion of 1497. The esteemed Cornish historian A L Rowse said of Perkin Warbeck:

The romantic figure of the youthful and handsome Perkin Warbeck has been celebrated in several plays and historical novels. Perhaps the best known of these is The Fortunes of Perkin Warbeck - A Romance by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, the creator of Frankenstein. The author takes Perkin's claim to be Prince Richard, Duke of York, at face value and names her tragic hero accordingly. Justifiably for a work of fiction, there are some historical inaccuracies. In this extract the siege of Exeter is extended into a third day and the size of the rebel army is exaggerated somewhat. The courageous efforts of the rebels are highlighted in contrast to the chroniclers who lionized the citizens for their valiant defence of Exeter.